Why Indian Publishing Needs to Get Less Fun

(This essay was published in July's Hindu Literary Review)

In the world of Indian English publishing, kitsch has begun to dominate the mainstream. Penguin India publishes 'Metro Reads', books that they call 'fun, feisty, fast'; Random House India produces the 'Kama Kahani' series of Indianized Mills and Boons; Hachette India openly states that it cares most about commercial thrillers; and with its latest, highly-marketed release, 'Johnny Gone Down', Harper Collins India seems to be headed in the same direction. These are all books that openly disclaim any particular literary merit. They are projected instead as 'fun' reads- with the implication that only a killjoy could possibly protest them.

A Preliminary Question

But before we get to that question- are these books fun for us?- there is an important preliminary question: why are they being offered to us? The easy answer is that the market is clamouring for them, just look at Chetan Bhagat. But this is too easy. It's been seven years since Bhagat's first book. Why would it take so long to follow his example? Moreover, the mainstay of Bhagat's readership has never been readers per se. It has been non-readers, those who are new to books, even new to the English language. This is certainly a massive group, and after Bhagat's success it has certainly been tapped- but by the smaller publishers, such as India Log and Shrishti Publications- not by the A-list. For them, Bhagat has simply been a fact of life- too dominant to ignore, too declasse to embrace. Which is one reason why their own 'fun' releases take great pains to explain that they're well-written too, that they 'bridge the divide' (a fashionable phrase) between the literary and the commercial.

In any case, with Bhagat's readership out of the picture, we can see more clearly that the push towards this new breed of writing is not being fuelled by market forces- those simply aren't strong enough. Our habitual readers of English fiction are not a small group, but they are not nearly so organized as to be pro-active in shaping publishers' decisions. Readers remain reactive and the freedom to decide what books get to them, remains primarily with the publishers. Unlike in more developed environments, 'publishers here need to be entrepreneurial', wrote Chiki Sarkar, Random House's Chief Editor, in an article in Seminar last year, 'A large number of our best-sellers have probably been commissioned ... Rarely do we discuss submitted work. Half of my list consists of subjects that I think would make a good book... And I would guess that’s the same for most other publishers here. [emphases added].' Her article, by the way, was called, 'Why Indian Publishing is so much fun'.

The impetus for new books, then, comes neither from the readers, nor from the writers- their submissions, remember, are rarely discussed. So how did the Kama Kahani series begin? Sarkar explains: 'We’re full of girls in the editorial department who had grown up on historical romances and hadn’t read any desi ones. So we figured we should launch our own.'

This answers our initial question. If, today, our shelves of Indian English fiction are crammed full of 'light reading', it is because our editors felt like it. That such centralization of literary power should hold sway in a world that includes readers and writers, seems unacceptable on the face of it- but let us hold our condemnation a moment. After all, more new Indian authors are being published today than ever before, in more genres than ever before. We have crime fiction, thrillers, young adult fiction, fantasy, chick-lit, erotica. These are books, says the Penguin Metro Reads Facebook page, 'that don’t weigh you down with complicated, boring stories, don’t ask for much time, don’t have to be lugged around.' They are what Hachette's M.D. Thomas Abraham calls 'crossover' books- not literature, but good enough to 'bridge the divide' between literary and commercial fiction.

No Such Thing

But what if there was no such divide? What if there was only good fiction and not so good fiction? What if being engrossing was a virtue, even in 'literary' fiction, and being shallow a vice, even in 'commercial'? Because the truth is, that the abstract standards of literary quality are constant. Campus novels and murder mysteries may be second-rate trash or the most moving experiences, but they aren't condemned by their labels to be a half-hearted compromise. So setting out to 'cross over', is simply setting out to lose your way. To try to 'bridge the divide' is to get on a bridge to nowhere. The galling element here, is not that you are arriving at mediocrity- there's no shame in that- but that you were aiming at it.

Getting Serious

If we remember further that Indian English fiction is a very fledgling body of work, greatly in need of direction and nurturing, then the escape to 'fun' seems even more of a cop-out. It suggests a basic lack of belief that quality books can be written by Indian authors- or an inability to recognize them. In the absence of a foreign endorsement, it is as though an unwritten rule prevails, that there may not be any serious writing, there may only be amusement. But such a self-loathing attitude helps nobody. It doesn't help the new genres. These can't be wished into existence by an editor looking for kicks; they must emerge naturally from those who care about them- like pulp fiction did, in the early American magazines. And it doesn't help the new writers, because there is a sad, but common, phenomenon, of authors being published and simultaneously disrespected. In the recent past, for example, there have appeared a number of essays lamenting the inferior state of Indian English writing. But the curious fact, which would be funny if it were not annoying, is that the same people who have contributed to that state have nodded along sagely, and sighed.

The point of this present essay is not, I hope, similarly futile. It is simply to argue that we ought to demand high standards from everyone associated with our literature: not merely our writers, but also our critics and editors. Then maybe Indian publishing can get serious.

Wednesday, July 7, 2010

Saturday, May 8, 2010

A Linguistic Awakening: Interview with Katherine Russell Rich

(Excerpts from this interview were published in The Hindu Magazine today)

American writer Katherine Russell Rich's 'Dreaming in Hindi' is an engaging, informative account of a year spent in Udaipur, learning Hindi from scratch.

In this email interview, she discusses the process and what it did for her.

1.You mention in your book that you weren't quite sure why you chose to learn Hindi in particular. But do you think your achievement, of re-imagining your world through a second language, would have been as personally rewarding if the language had been some other?

Yeah, I kind of stumbled into Hindi—I didn’t know precisely why. I wasn’t one of those Westerners who was after all-things-Indian to get jolts of spiritual enlightenment. I just liked the way the language felt in my mouth, I liked the glimpses it gave me of someplace so different from what I knew. It’s funny to say this about something as cerebral as learning a language, but I liked the sensual experience of Hindi.

I sometimes think when we allow ourselves to stumble into something, we leave ourselves open to larger forces guiding us in the right direction... Hindi and India were an absolutely essential part of the mix, it turned out. But no way would I have anywhere near the same rewarding experience had I gone, say, to Cuernavaca to learn Spanish. Hindi and daily Indian life are so infused with the wisdom of the Vedas, that wisdom seeps in whether you’re looking for it or not. And whether you intend for it to or not, it’s transforming. In casual conversation, for instance, somebody said to me, “Life is a rope snake,” and I haven’t felt fear with quite the same intensity since. And as a proper, distanced Anglo-American, I was at first horrified by, then totally melted by the boisterous closeness of an Indian family. I ended up loving that and yearning for more.

2.As someone who balks at the idea of learning another language in adulthood, I was very struck by your analysis of how traumatic a process this is, and how it requires unsettling your whole way of thinking. Do you think you could have done it if your own life had not been at a cross-roads at the time?

Being at a cross roads gave me the time to get away, but I’m not sure it’s what enabled me in the process. It might sound weird, but I think what came in most useful was the fact that I’ve had cancer for two thirds of my adult life. When you live with cancer, you have to figure out ways to live with constant uncertainty, and same thing goes for when you learn a language: Did that man just say what I thought he said? No way. Wait, wait: I think he did. In both instances, you either learn to be fluid or you go nuts. In my case, I’d already gotten a jump on learning to be fluid when I started learning Hindi.

3.It's often said that we in India must all learn a common language if we're going to get over our linguistic rivalries. But since this can be such a painful process, would you say a 'live and let live' philosophy is a better approach?

A live-and-let-live-philosophy is a better approach in theory, but I’m not sure it is in practice. For a country to truly function, doesn’t it need to have some kind of collective national voice? On the other hand, just as you can’t invent a symbol, you can’t thrust a language on people. A language is so much a part of the unconscious, it has to be gently incorporated or it’ll never seep into the deeper levels.

As India continues to change so rapidly, I have a feeling the situation with languages might too, maybe because there’ll be more incentive to have a common language. It won’t be a matter of ramming it down people’s throats. It’ll be a necessity for doing business.

4.Reading your book, it's obvious you love English. In a paradoxical way, do you think that helped you with your Hindi- knowing that it would always be at arm's length, so to speak?

I do love English but I think that’s largely because, like a lot of writers, I love language. And loving language, no question, helped me with Hindi. Unfortunately, I think that knowing English would always be my primary language slowed me down with Hindi. If you’re a Hindi-only speaker and go to America, you can’t cheat and fall back on Hindi when you get sick of fumbling through in another language. But if you’re American and go to India, you can always corral someone into speaking English with you, to the detriment of your Hindi.

5 .Has your time in India learning Hindi changed your use of English?

In the beginning, that was happening all the time. You know how people in India often say “Hum” in a sentence where English speakers would say “I”? I was constantly doing the reverse—“We’ll be there at 7, then”--and people would say, puzzled, “We? Who else is coming?”

I was in such an Indian frame of mind, it took me about a year to know how to begin the book. One small example: I’d gotten used to the Indian sense of hierarchy and so I kept balking at writing about my teachers in any way that might sound disrespectful. This is the dead opposite approach you want to take with an American audience, who’ve been seeped in notions of “everyone’s equal” their whole lives.

I finally snapped out of it when one day, I was telling a writer friend a very rude but very funny story about one of the teachers and she said, “Of course you’re going to put that in the book?” Without thinking, I answered, “Oh no, that would be disrespectful,” and she cried, “What. Are. You. Talking. About?” After that, I was back in America.

Book Review- Maria's Room, by Shreekumar Varma

(First published in April's Hindu Literary Review)

Not many novels are able to combine good writing with good story-telling. Maria's Room comes close- which makes the shortfall easier to sight. This atmospheric, highly literary novel is also an example of a mis-crafted narrative, which, while containing all the elements of a powerful story, doesn't effectively arrange them.

A Potent Setting

But the elements are there. Shreekumar Varma sets his book in rain-lashed Goa, an inspired choice of setting for a protagonist on a breakdown. Far from the revelry of sun and sand, this is a Goa of overflowing streets, vivid foliage, lonely, courteous hotels. It is the perfect place to brood, and that is our narrator's intention. Following his arrival in Goa, he takes us through his sojourns to the town, his encounters with locals and fellow guests, and his abiding introspections. He is Raja Prasad, a novelist searching for material for his next book, while wrestling with the failure of his last- and more than that, with the scars of personal tragedy. Soon he shifts into 'Maria's Guesthouse', and drifts into an affair with a young girl, even as he learns the story of another love, from another time. But the events of the past are impinging on the present, and the novel that Raja is writing begins gradually to lay bare his own predicament.

The Unreliable Narrator

However, as readers, our grasp of the demons that assail Raja- either what they are, or where they come from, or what is strange about them- remains only vague until late in the book. Realistically, this is not a problem- an afflicted narrator need not be particularly informative. But the question, from an artistic perspective, is whether he is then fit to narrate. Imagine, for example, a party at which a man is drunk out of his wits and involved in a series of fascinating scrapes. He is certainly the subject of a great story- but he is no position to recount it. We would much rather listen to a more sober onlooker, someone capable of marshaling the facts.

Something similar is the central defect of Maria's Room- a defect of story-telling. Raja tells us too little, until it is too late. Even the murkiest mystery arises from facts, and our interest in his situation could only really be piqued if we knew something solid about it. But his narrative, though rich in thought and observation, is short on facts. We are led to a conclusion without ever being primed for it. And when we finally understand, not just the secret of Raja's pathology, but the bare details of it, we wish we'd been told before.

Skill and Sympathy

Even saddled with this defect, though, the book remains very readable. Partly this is testament to Varma's skill with words. He brings to life the primal energy of Goa in the monsoons, so that even when the story flags, the atmosphere holds. His descriptions, as a rule, are precise and vivid: the rain 'writhes' against a window, a breeze 'dances' across a swimming pool, lights glow 'damply.' His language has flair: a cell phone is shaken 'like a faulty thermometer'; interrupting a compulsive talker is likened to 'boarding a train in motion.' But more than writing well, Varma cares about his protagonist- and that feeling communicates. Raja may be an enigma to us, but he is appealing in his vulnerability, and his open acceptance of it, as, for example, in his relationship with his father. Not many thirty one year old men could accept their parent's constant concern, and yet come across courageous. And not every writer could write them like that. Which is why, despite its errors of craftsmanship, Maria's Room is well worth visiting.

Saturday, March 27, 2010

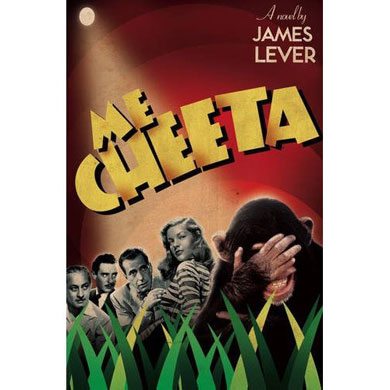

Book Review: Me Cheeta, by James Lever

(This was published in February's Hindu Literary Review)

A one line description of Me Cheeta- the 'autobiography' of the chimp in the Tarzan movies- would suggest it is more or less a gimmick. Surely a book that proceeds from such an unreal premise cannot be taken seriously. In fact, it can. There is (as far as we know) no such thing as a monkey capable of language and literature, but then nor is there any such thing as an orc or an elf, or Jane Eyre, or Hercule Poirot, or Sartaj Singh, or Rocket Singh. They are all equally made-up, and one of the pleasant things about a book that is unabashedly fictional is that it reminds us what the essence of fiction is. Artifice. Whether you take for your protagonist a grim, tough-bitten man of the world or a goofy chimpanzee in Hollywood, the question is never: Is it real? The question is only: Does it tell the truth?

On the other hand, there is a reason why most fiction deals in the recognizable, which is the need to keep in touch. The more 'far-out' a character becomes, the less likely it is to serve any useful purpose. It is one thing to imagine a chimpanzee writing, it is another to imagine it writing three hundred pages of interesting memoir- without metamorphosing, at some point, into an ordinary human being. In which case we would be entitled to ask why it wasn't simply one to begin with. So when James Lever decides to get into the head of Cheeta, a chimpanzee abducted from the jungles of Liberia and launched into show-business, he is taking on a task that is legitimate, but difficult. On the whole, he does an excellent job of it. He does it by sticking, more or less, to the core ground of true emotion that Cheeta is perfectly placed to know- a captive animal's feelings for humanity.

This is, however, the less prominent theme of the book. The prominent theme, as advertised on the back jacket and in the bulk of the blurbs, is that of a Hollywood spoof, a parody of a celebrity memoir a bitchy, satirical send-up of the Golden Age of the Dream Factory. And it is true that no one who picks up this book hoping for the salacious atmosphere of gossip is likely to be disappointed. From the introduction, where Cheeta resolves to tell his tale 'without bitterness, name-calling or score settling', 'no matter how oafish the behaviour of certain people, such as Esther Williams, Errol Flynn, 'Red' Skelton, 'Duke' Wayne...', to his continually back-handed praise of his 'colleagues' ('Chaplin is an extraordinarily special human being... but... not even Charlie's stoutest defenders would claim that he was perfect or even likeable or indeed defensible on any level at all'), the entertainment is undeniable.

However, it does not fit. To put high-grade insults in an animal's mouth is funny, but strictly fanciful; the animal in such cases is the prop, not the author. A little less fanciful, but still a stretch, is Lever's portrayal of Cheeta as a delusional and increasingly bitter actor. His cluelessness about how Hollywood really works, coupled with his sense of being at the centre of it, is intended, perhaps, to echo the situation of many of the industry's human stars. But this can only succeed as a brief joke: no really insightful analysis of an artist's struggle in Hollywood can emerge from Cheeta. He is, after all, only a chimp.

All in all, these elements of the book are best treated as stand-alone parodies, snatches of information and comic relief, and if they were all there was to Me Cheeta, it wouldn't have deserved to make the Booker long-list. But there is more. The beating heart of the novel is Cheeta's relationship with humanity, and in particular with Johnny Weissmuller, MGM's Tarzan. “Happy, beautiful, young, untroubled”, Johnny is the centre of Cheeta's world, the human being who epitomizes the best of human beings, the only species that, for all the killing and hurt they cause, truly love and need animals. When Cheeta says this, we hear no satire. His gratitude to humans, and his fascination with their world, is both sincere and believable. Anyone who has cared for a pet will comprehend it. And Lever knows the profundity of this relationship, which is easy to ignore, but worthy of a novel. He sums it up in the lovely end, where Cheeta recalls the memory of a baby, lost in the jungle. “Its trusting gaze was the most vulnerable thing we'd ever seen, but there's power in that... The thing starts to cry... It smiles... I pick it up. It needs me, I think. I'll be its friend..."

Sunday, January 10, 2010

Book Review: Neti, Neti, by Anjum Hasan (IndiaInk, 2009)

(This was written for Biblio)

Towards the close of Neti, Neti, its young protagonist Sophie Das wonders aloud when her story will end. A little later she has a moment of realization: it won't even be on the last page. She is right about this, and perhaps unwittingly she reveals in the process the truth of her tale. Not merely that it remains unresolved, but that she does not know how to resolve it. So she cries for help- as she has been, more or less clearly, more or less consciously, all through the book.

Here, in a nutshell, is the best and worst of Neti, Neti. It takes on a problem that it cannot tackle, and on this stark measure it is a failure. But the problem isn't easy, and the attempt is honest, so there is not much shame in the defeat.

What is the problem? It isn't anything very new or startling; it is the problem of a young person getting to grips with adulthood. More than anything, Neti, Neti is a coming of age book. Indeed, one of its chief virtues is that amidst a literary culture so paranoid of 'self-indulgence', it features a protagonist who makes no apologies for worrying about herself. Not unlike the author, Sophie is a young woman from Shillong, who moves to Bangalore in search of freedom, and vistas wider than the home. The city gives her independence alright, and Sophie knows how to value it. In her apartment, “she could cook what she liked, smoke to her heart's content, put every object exactly where she wanted it to be and know it would not move unless she moved it.”

But it gives her other things beside; all the hot and bother of a chaotic Indian metro. Traffic jams, accidents, casual rudenesses, ugly malls, dirty streets, vast economic and social disparity existing cheek by jowl. Like any sensitive young person, Sophie feels the oppression of her environment and fears it will overwhelm her. She thinks with a pang of her beautiful home-town and the life she left behind. Hasan knows what hurts. The thousand little pin-pricks, Sophie's everyday humiliations, are all as they should be.

They are not, however, exactly as they should be. From fairly early on, we see the signs that Sophie is not trying hard enough. There is something unduly exaggerated about her horrors, the city seems to parade its evils especially for her. Hasan's insinuation is that other people look away, but the truth appears to be that Sophie looks too raptly. There is a glitch in her perception that repels our sympathy, and it is most apparent in her attitude to wealth. We have all felt the aesthetic failings of a lavish mall, but we have not all been literally paralyzed by the sight. It is reasonable to flinch at Page 3 culture and the glossy lifestyle magazines; it is not reasonable to devour them, just so one may vent. “She ground her teeth reading about wine appreciation evenings in swanky hotels.” This is funny, until you realize it is serious. “Nausea, mixed with awe”, is Sophie's avowed reaction to “wealth, in all its forms.” She does not pause to consider whether this isn't a bit excessive.

For us, however, it is worth pausing here, because it affords a clue to Sophie's character. What might be the probable cause of her heightened intolerance towards 'things'? Perhaps, the book suggests, it is the contrast they strike with her sheltered childhood in Shillong, and its slow-moving, small-town values? This is certainly part of the explanation, but it does not seem the whole or even the greatest part. After all, we are told that Sophie left Shillong precisely because she felt that there, “there was nothing to see.” Moreover, it is not necessary to be brought up in a small-town to feel, in your youth, the crush of the city. Every childhood has its own shelters, and the transition to adulthood is always a shock. And yet, staring at an array of packaged items on a supermarket shelf, walking by lighted shop-fronts, whether in a mall or not, most people, now and then, will feel a rush of something akin to admiration. An abundance of 'things' need not only be proof of human greed. It is also proof of human achievement. So for a truer explanation of Sophie's trouble we must look to her character, not her circumstances. And there is one glaring fact that can strike a twenty five year old like an arrow through the heart as she looks around at all the glut of productivity- and sees nothing made by her.

If one is self-critical enough to grasp this, the way ahead becomes easier to see. It lies in cultivating one's own abilities. Unfortunately for Sophie and for her story she is rarely self-critical, and she is frequently selfish. As a result, her friends and acquaintances, in whose sympathies she might have taken recourse, remain two-dimensional figures. She seems to want them around chiefly in order to feel superior to them- with their prosaic dreams of money and comfort. Her interest in their interior life is half-hearted at best. So even when her friend Ringo kills his girlfriend Rukshana, her thoughts are neither with him, nor with her, but with herself. “All Sophie could think of was the part she had played.” There were a few quarrels between the three, but to the reader it seems no part at all.

But perhaps the most apparent instance of Sophie's self-centred-ness, is her relationship with her boyfriend, Swami- “the first boy who understood the essentially shitty nature of her job and held her hand when they crossed roads.” Given that this isn't much to build on, it is unsurprising when later she grows dissatisfied with his easy-going personality. But the idea that, in letting the relationship drift, she might now be simply using Swami does not cross her mind. Instead, Sophie blames her boyfriend for failing to weaken in his “rock hard love”, because of which, she complains to herself, “nothing need ever change.” All in all, she is rather passive. She expects things to please her; she does not think of being pleasing herself.

That she remains an engaging protagonist, is the reason that Neti, Neti remains a good book. Hasan is not alive to her character's faults, but her achievement is that she makes the reader want to be. We are interested in criticizing Sophie because we are interested in her. And that is because she is honest. She is unhappy, but she does not pretend otherwise- as many people do. Moreover, she wants to feel better and she is willing to look for help. To deserve sympathy and attention, no more than this is required. So when Sophie decides to return to Shillong, we still follow her with interest. There is the possibility that the mountain town is her true home, 'that certain places on earth must bring forth happiness, as a plant peculiar to the soil, that cannot thrive elsewhere.' There is also the possibility of love; a man whose image she carries in her heart.

Now, Sophie's capacity to imagine these possibilities, and to act upon them, is proof of a creative impulse- the kind of capacity that could really turn her life around. But an impulse is only a spark; if it is to burn steadily it must be nourished. And it cannot be nourished unless at first it is shielded. This she does not do. She is greedy to be rewarded, and so her enthusiasm remains feeble and easily dashed. No sooner is she at her parents' home than we find her staring out of the window at a changing town, “at cold, boxy, pink and concrete houses built by people who didn't care about Beauty.' This is vintage Sophie. In the days that follow she is witness to domestic strife and local politics, and the end of an affair. There is no cold rejection; the man cares deeply. There is no familial tragedy either; her parents, despite hiccups, are sticking together. But it wasn't as she had imagined it, and so Sophie decides that “she was alone from now on. She was her own context.” Armed with this insight, she returns to Bangalore, to another job that she does not like.

Her new attitude, though, is “to grow mesmerised by the boredom.” “Nothing frightened her anymore- not walking into a shop in a plush mall, trying on clothes and then buying nothing. Not waking up in the middle of the night and being unable to go back to sleep. Not seeing a man crushed to death on the street.” The old ambition of happiness is gone, and like an invalid, Sophie has taken to being grateful for small mercies- the odd free ride, the occasional kind word. 'I don't want to feel the knife edge of anything ever pressing into me again', she thinks, as the book ends. They are hardly fighting words.

Of course, we are expected to sympathize with Sophie's disaffection, and even perhaps to applaud it. 'Neti, Neti', the title of the book means 'Not this, Not this.' Bangalore is ugly, Shillong is petty, so what is one to do? But the whole premise of this philosophy is flawed. It only wants to receive; it does not think to give. As readers, we never feel that Hasan sees this, and that is why, ultimately, Neti, Neti is a failed story. But we also never feel she is happy with the failure, and that is why it is a good story.

___________________________________________________________________________________

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)